Total mess: the ‘unintended’ problem with deposit return schemes

A deposit return scheme (DRS) is a recycling incentive program where consumers pay a small deposit when purchasing beverages in single-use containers like plastic bottles or aluminum cans. This deposit is refunded when the container is returned to a designated collection point.

The idea is simple; by placing a monetary value on packaging waste, consumers are encouraged to return and recycle their containers instead of discarding them.

Countries like Germany, Norway and Canada have successfully implemented DRS. For instance, Norway boasts a 97% recycling rate for plastic bottles thanks to its well-established DRS.

The goal of a DRS is to reduce litter, improve recycling rates and create a more circular economy for packaging materials.

Some European countries have reported recycling rates upwards of 90 percent thanks to well-implemented schemes.

In the United States, many see DRS as a common-sense approach to reducing the billions of containers that end up in landfills, waterways and neighborhoods each year, but some cities are experiencing major problems and DRS schemes are in a real mess; literally.

Despite their benefits, DRS programs can have negative and unexpected consequences, especially in urban areas where poverty and homelessness are widespread. The people worse affected tend to be local residents and business owners as well vulnerable people in the area.

1. Littering and mess around trashcans and containers

In cities across North America, Europe and Australia, trash cans and dumpsters are frequently broken into by individuals searching for containers with deposits. The contents are often left scattered on sidewalks, requiring municipalities to spend millions on clean-up and repairs.

It has become commonplace for containers to be upended onto front yards “just in case there was [a bottle or can] at the bottom”. Businesses and residents in the areas affected, have reported disruption from constant rifling through public trash, leaving surrounding areas strewn with messy garbage and a dramatic increase in litter on the streets.

2. Rummaging and unsafe behaviors

Reports from countless cities describe people digging through public trash cans, residential recycling units and even private dumpsters. The risk of injury involving syringes, broken glass and other hazardous materials is huge.

In Ireland, signs have even been erected at train stations, specifically warning people of the risk of being pricked by syringes when rummaging for bottles and cans to return. The risk of unsafe or unsanitary discarded trash is high, as is the risk of injury to people climbing on or inside dumpsters and waste units, in their hunt for bottles and cans.

In central Dublin, the sight of people rummaging through trash became commonplace after the introduction of the Deposit Return Scheme. A local business owner noted that the DRS, while helpful to vulnerable people, has created a “beast” within Dublin city center.

“There are groups of people arriving with [hex] keys and they are there sifting through… looking for stuff… every morning there are people emptying [trash] around the place. It really is mad.”

3. Conflicts and public safety issues

A similar report from Melbourne, Australia, explained that an increasing number of people have taken to trawling through households’ trashcans in a bid to find cans and bottles eligible for the government-run container return schemes, with some earning large sums.

It is said that due to increased competition, some people are going to extreme lengths to acquire containers, a trend proving highly divisive among communities.

In some cases, disputes have broken out between individuals or organized groups competing to collect high volumes of returnable containers. Altercations near collection units have become common, with residents and businesses voicing concern over safety and violent behavior.

Police in Portland, Oregon, have attended multiple call outs due to assaults on staff and ongoing safety issues at certain returnables depots. The atmosphere is described as tense.

In many areas where return schemes have been introduced, there has been an increase in threatening and violent behavior, with different groups clashing over the more accessible bottles and cans.

While many of those going through trash are people with addiction issues or homeless, informed sources said that organized begging gangs are now operating across cities, collecting as many containers as possible.

4. Perverse incentives

Environmental activists have warned that widespread deposit systems could in fact produce a “rebound effect” that would encourage consumers to continue, or even increase, their buying of plastic bottles.

Deposit refund systems are not, “miracle solutions”, says Manon Richert, communications manager for the NGO Zero Waste France. “This system can certainly help improve recycling figures, but it doesn’t target the goal we need to have, drastically reducing our production of plastic.”

For years, we have been fed a discourse that presents waste sorting and recycling as an easy green gesture, and we have spread the idea that buying plastic isn’t so bad if we recycle it. And now, we’re going to add a financial incentive,” she says.

Critics warn that deposit schemes may inadvertently encourage overconsumption. Evidence from Germany suggests that the rise in deposit-eligible containers may be contributing to an increase in single-use plastics, undermining long-term sustainability goals.

5. Economic vulnerability

For many experiencing homelessness or financial hardship, collecting deposit containers becomes a vital, if precarious, source of income. This often places vulnerable individuals in unsafe environments and creates friction with the broader community.

Here in the U.S., as well as in cities across the globe where return schemes are in place, the process of collecting and redeeming recyclables is the go-to method of income for people living on the streets. The huge spike in those collecting and returning cans and bottles means that vulnerable people find themselves reliant on collecting and competing with other vulnerable groups as well as organized gangs.

In Germany, reports state that poverty and loneliness are driving the unemployed and elderly onto the streets in search of the discarded deposits, which they can exchange for cash. Social experts warn of the welfare crisis this suggests.

A report from the Bay Area in San Francisco, describes fairly standard hours for the homeless who redeem, scouring the streets all night from 11pm – 7am. Some tour the neighborhoods and sort through the blue containers that line the street for impending trash collection and others drain the public garbage cans and private dumpsters for recyclables.

Discarded garbage becoming a resource for those less well-off, puts vulnerable people at even greater risk when searching for items to recycle.

To maintain the environmental benefits of DRS while addressing these issues, municipalities and designers are exploring more resilient infrastructure solutions:

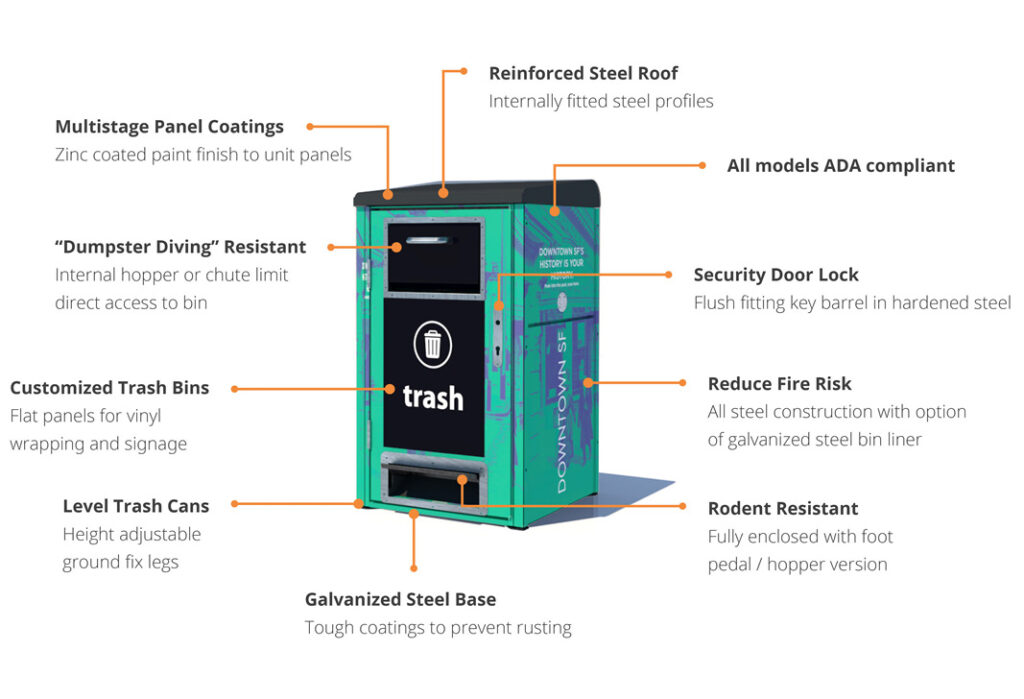

Raid-resistant container units

Secure, tamper-resistant collection units can deter break-ins, prevent injury and protect public space from litter and damage. These units are designed to withstand forced access and reduce maintenance costs.

By incorporating carefully designed openings that only allow items to be inserted (but not retrieved), these systems minimize the potential for rummaging and improve safety for both the public and collectors.

Equity-focused approaches

Some programs are beginning to consider more inclusive strategies. Community-managed collection points for deposits, job training tied to redemption centers and policies ensuring safe, regulated access for low-income individuals can help balance public order with compassion.

Expanded return infrastructure

Increasing the number of return points, particularly at stores, transit hubs and community centers, can reduce pressure on public trash points and offer more controlled, hygienic collection environments.

As more U.S. states and cities prepare to implement or expand deposit return schemes, these lessons from around the world serve as a critical reminder: thoughtful design, community input and equitable planning are essential to ensure that DRS programs succeed not just on paper, but on the streets.